Reason In Our Dark Time

Interview by Richard Marshall.

'A great deal of our math, science, philosophy, and everyday behavior presupposes that stability and equilibria are the “default” states, and everything else involves some “perturbation.” This is a mental model, a conceptual frame, a tacit belief, a presupposition—whatever you want to call it. We live on a restless planet in a violent universe. Most of what we think of as distinctively human has occurred in the last 10,000 years in the Holocene—a period in which the Earth was abnormally quiet. If we’re interested in the continuation of the human experiment we need to focus on resilience and coping with change (whether natural or anthropogenic) rather than living as if God or nature has given us a nice, orderly, calm, Babbit-like existence.'

'The problem is that the Enlightenment dream may make too many demands on poor African apes like us. We may just not be up to it. In the last few centuries we’ve managed to reduce how much we kill each other, we’ve learned some basic lessons about public health, and life is relatively good for more people than ever before. But since we’re not very good at something as basic as controlling our reproduction, life is also really bad for more people than ever before.'

'One of the real dangers of our time is people’s indifference to history. Let’s just be blunt: People with long memories and a vivid sense of the past have an immediate understanding of politicians like Trump. They are not surprised by the behavior of Google, a corporation that notionally (until recently anyway) espoused the slogan “don’t be evil” and then runs over individual people and even entire nations in the pursuit of profit. Even our own discipline has become dehistoricised.'

'The idea that we would raise billions of sentient animals, treat them horribly, pollute our waterways with their waste, compromise the effectiveness of our antibiotics so that they grow faster, and then slaughter them with little regard to their suffering so that we can feed off their corpses, will seem to most people unthinkably cruel and barbarous—sort of in the way that we think of medieval punishments, or Europeans today think of the death penalty.'

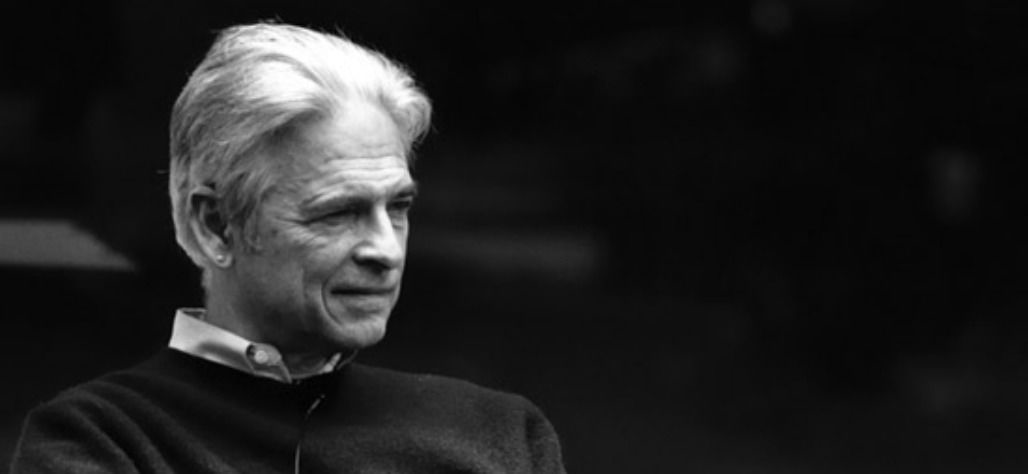

Dale W Jamieson is Professor of Environmental Studies and Philosophy, Affiliated Professor of Law, Affiliated Professor of Bioethics, and Chair of the Environmental Studies Department at New York University. He is also Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Dickson Poon School of Law at King’s College, London, and Adjunct Professor at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia. Formerly he was Henry R. Luce Professor in Human Dimensions of Global Change at Carleton College, and Professor of Philosophy at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where he was the only faculty member to have won both the Dean's award for research in the social sciences and the Chancellor's award for research in the humanities. He has held visiting appointments at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Cornell, Princeton, Stanford, Oregon, Arizona State University, and Monash University in Australia, and is a former member of the School of Social Sciences at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Here he discusses philosophical issues of climate change, the anthropocene and the Enlightenment, why history matters, barriers to meaningful action, whether climate change is an economic matter, whether climate change is too big for ethics, climate change and international politics, the anthropocene and agency, loving the apocalypse, the banality of climate change, why philosophers should be heeded in the environmentalist debates, animal ethics, the split between animal liberation and environmental ethics, progressive consequentialism, duties to the desperate and differences and agreements with Peter Singer. This is a walk to some big cliffs...

3:AM:What made you become a philosopher?

Dale W Jamieson:I grew up as an only child of two parents who had dropped out of high school. They had enormous respect for education and encouraged me as a child when I had strong interests in both math and science, but we really didn’t have much by way of educational role modeling in our family. I became religious and at 14 went to a boarding school 500 miles from home to begin theological studies. By the time I started university, politics had replaced religion in the economy of my enthusiasms but I had no idea what to study. My boarding school emphasized languages which I was bad at, and deemphasized math and science which I was good at. I played with English and Sociology in college but dropped out to work in the anti-war movement. I was going around denouncing the Viet Nam war as immoral but one day it dawned on me that I didn’t know what that meant. I signed up for an ethics class at San Francisco State to find out the answer. My teacher was Anita Silvers. She hooked me on philosophy and I was a goner. I took every course at San Francisco State from Carnap to Mao, went to London and studied Wittgenstein, and wound up at North Carolina where I studied ethics with W.D. Falk and everything else with Paul Ziff with whom I wrote my dissertation in philosophy of language. Paul was the smartest and most passionate person whom I had ever met, and he refused to accept the idea that life has compartments: work, play, home life, philosophy, science, the conceptual and empirical—they all rubbed shoulders. A single day would be filled with philosophy, art, and probably too much bad behavior. The point was to get to the bottom of things, not to be a “philosopher”—much less a philosopher with a specialization.

3:AM: Your big philosophical concern is the environment. Things are looking bleak at the moment. You’ve written about climate change – and it’s taken a long time to complete your book on this. You like the joke that says that you can’t write the story of climate change until you knew how it ended – and you say that it dawned on you that its living in a world of change that matters. Can you say something about what you mean by saying we must live with change and why this is a different presupposition to contemporary approaches to science, epistemology, ethics and politics.

DJ: A great deal of our math, science, philosophy, and everyday behavior presupposes that stability and equilibria are the “default” states, and everything else involves some “perturbation.” This is a mental model, a conceptual frame, a tacit belief, a presupposition—whatever you want to call it. We live on a restless planet in a violent universe. Most of what we think of as distinctively human has occurred in the last 10,000 years in the Holocene—a period in which the Earth was abnormally quiet. If we’re interested in the continuation of the human experiment we need to focus on resilience and coping with change (whether natural or anthropogenic) rather than living as if God or nature has given us a nice, orderly, calm, Babbit-like existence. When you look at things that way you wonder why “process” philosophy rather than “time-slice” philosophy hasn’t gotten more attention. One reason, perhaps, is because most “process” philosophy is historicist (e.g., Hegel) and not concerned with “deep time.” Maybe Whitehead is an exception. He may be a really important philosopher for all I know. I’ve never been able to read him.

3:AM: You argue that the issue is an issue of the anthropocene. Is our world the Enlightenment dream turned nightmare?

DJ: The Enlightenment dream is a good one. The idea that people should rationally appreciate their place in nature, assess threats and possibilities, and regulate their behavior in response is inspiring. One of the epigraphs in my book, Reason in a Dark Time is taken from Dewey:

The very essence of civilized culture is that we…deliberately institute, in advance of the happening of various contingencies and emergencies of life, devices for detecting their approach and registering their nature, for warding off what is unfavorable or at least for protecting ourselves from its full impact….

The problem is that the Enlightenment dream may make too many demands on poor African apes like us. We may just not be up to it. In the last few centuries we’ve managed to reduce how much we kill each other, we’ve learned some basic lessons about public health, and life is relatively good for more people than ever before. But since we’re not very good at something as basic as controlling our reproduction, life is also really bad for more people than ever before. The density of human population combined with the development of powerful and largely unconstrained technology has given us the problems of the anthropocene and the serious possibility of self-caused extinction. Aristotle thought that humans are rational animals and Hobbes thought that we act on the basis of rational self-interest. If only! It’s not that we never do these things, it’s that they are hardly constituative of who and what we are. The Enlightenment is not a nightmare, nor is it something that comes easily to us. It is an aspiration—and a good one!

3:AM: Why is it important that we understand how we got into this mess?

DJ: We live in a world in which everyone wants solutions. But we can’t find solutions if we don’t understand the problems, and we can’t understand the problems without knowing how we got here. One of the real dangers of our time is people’s indifference to history. Let’s just be blunt: People with long memories and a vivid sense of the past have an immediate understanding of politicians like Trump. They are not surprised by the behavior of Google, a corporation that notionally (until recently anyway) espoused the slogan “don’t be evil” and then runs over individual people and even entire nations in the pursuit of profit. Even our own discipline has become dehistoricised. We think of history as another specialization, like philosophy of language, rather than as something that informs everything we do and think. Even those who specialize in the history of philosophy often ignore the political and cultural context, and the natural world in which their philosophers were philosophizing. This has consequences both trivial and important. If you systematically read the last fifty years of the major journals in our discipline you would be amazed at the amount of redundancy. Most of this is unacknowledged because most of us know so little about the history of our discipline and even the subfields in which we work. We know the “great men” and a handful of heavily cited papers in our specialization. When there is a historical frame around a paper it’s often a caricature that has become canonical. If we don’t have historical consciousness we can’t really understand problems in all their dimensions, and if we can’t understand problems than we can’t find solutions.

3:AM: What are the barriers to meaningful action?

DJ: When it comes to climate change it’s all the usual barriers: greed, mendacity, ignorance, short-sightedness and so on, manifest in the extreme power of corporations, the weakness of government, and the indifference of citizens. But it’s also true that climate change is an unprecedented problem so it’s not surprising that it’s so difficult to address. Our traditional systems of decision-making are just not up to preventing changes in fundamental earth systems that are driven by a constant barrage of individually negligible emissions of an invisible, odorless gas, by billions of people all over the world.

3:AM: Should we approach climate change as an economic issue?

DJ: We need to use economic instruments such as carbon taxes, cap and trade, tax and dividend and whatever else to help incentivize behavior that will move us to a post-carbon, post-animal agriculture world, and make our societies more resilient to the shocks that are already baked into the system. But that doesn’t make climate change an “economic issue.” Climate change involves fundamental choices about how we want to live and what kind of world we want. We can use economic instruments to help realize our goals but economics does not tell us what our goals should be.

3:AM:Is the issue too big for ethics to grasp?

DJ:Ethics is prescriptive and can change behavior, but usually only at the margins. Ethical systems are fundamentally conservative and primarily directed towards regulating interactions within communities. Climate change involves behaviors that are individually negligible, whose impacts go far beyond the spatial and temporal constraints that define our sense of community. People who go around saying that it is wrong to fly and to eat meat are not so much making appeals to us from within our shared morality, but engaging in something more like “persuasive definition.” They want us to look at the world and ourselves in a different way. Someday these prohibitions against flying and eating meat may be written into our moral psychology, but it will only be after there are viable, widely shared alternatives that are beginning to be widely adopted. Until then, there will be “start up” moralities that a few people conform to which may eventually become dominant, but they will not have much effect on broader patterns of behavior. Moral revolutions are typically seen retrospectively. Prospectively, the revolutionaries tend to look like crazy people, and sometimes they are.

3:AM: You’re kind of pessimistic about the ability to get the policies and actions and thoughts in the right shape to do anything about climate change. You see this as one of but not the only threat arising from the anthropocene. What do you mean by that term?

DJ: There are two senses of the term ‘anthropocene’ that need to be distinguished. In one sense it refers to a geological epoch which we may now be in, that is marked by a distinctive layer in the Earth’s crust. Whether or not we are in the anthropocene in this sense will be formally decided by the International Commission on Stratigraphy later this year. In another sense ‘the anthropocene’ refers to the way we live now, in a highly globalized world, characterized by a large human population and powerful technologies that allow for “action at a distance” that aggregate apparently negligible acts into powerful forces that are transforming fundamental planetary systems. In this sense ‘the anthropocene’ refers to a period in which nature as an independent autonomous domain comes to an end or is under serious threat.

3:AM: What do you make of Posner and Weisbach's notion of International Paretianism? Why you don't think their conclusions follow from what they suppose. And why do you think the most important climate change policy will happen within rather than between countries?

DJ: Like many of those who write about international relations, Posner and Weisbach seem to view states as agents that have interests that can more or less be objectively identified on the basis of what benefits or burdens them economically. I think this is way too simple. In this era of globalization we are witnessing struggles within individual states about what their identity and interests consist in. Is it in the interests of Britain to leave or remain in the EU? As we saw in the referendum, there are different Britains and they see their interests in different ways. For a lot of everyday blokes the EU affected their sense of identity in ways they disliked, and they were right in thinking that the EU didn’t return much to them by way of economic benefits. It is probably true that the economic benefits of being in the EU are a net positive to the UK, but a large number of people do not share in these benefits and the result is increasing inequality.

So is it in the UK’s interests to leave the EU? It depends on your values. The answer can’t be read off of GDP statistics under various scenarios or some measures of global influence. Citizens often think of a state’s interests in terms of the promotion of ideals such as democracy, a particular way of life, or other values which they endorse or see as part of their historical continuity and identity. In this domain as in others values are not fixed, and so a state’s interests are dynamic and in a constant state of negotiation and construction. If you have a flat, fixed view of state interest then it is difficult to understand why some states adopt aggressive climate change policies, even when that risks economically disadvantaging them, and other states do not even when it would be in their economic interests to do so.

If you look globally you see a patchwork of jurisdictions (nations, states, provinces, cities) that have taken aggressive action on climate change, and a patchwork of jurisdictions that have not. These various policies reflect the politics of each jurisdiction and the values of its citizens. The Paris climate conference in December, 2015 was a recognition that countries bring their climate policies to international meetings rather than create them during the negotiations (much less do they receive orders from the international community and then go home and implement them). Every country now has its own domestic political debate about how to respond to climate change. This is where the action is.

3:AM: Does living in the anthropocene change everything to do with ethics and how we need to think about how to live?

DJ: The most fundamental challenge of the anthropocene concerns agency. For those who lived the Enlightenment dream (always a minority but an influential one), agency was taken for granted. There were existential threats to agency (e.g., determinism) but philosophy mobilized to refute these threats (e.g., by defending libertarianism) or to defuse them (e.g., by showing that they were compatible with agency). Philosophical work in this area provided the foundations for the positive law that largely still prevails, by mapping the contours of agency, specifying the conditions under which it may be compromised, and tracing the interpersonal and social consequences of these considerations. The bizarre thing about the anthropocene is that never has humanity been more powerful and never have individual humans felt so powerless. This is because so much that drives the circumstances of the anthropocene is the aggregation of apparently negligible acts, often amplified by technology, rather than decisive acts by autonomous decision-makers. The erosion of agency also has consequences for our politics. As a result of all this, the fundamental ethical challenge of the anthropocene is the recovery of agency, or alternatively to come to terms with its loss and to understand how to go on.

3:AM: You argue that going forward we need to be pragmatic even though things must change. Abatement and mitigation, adaptation, policies piggybacking on other actions and importantly the perfect not to be the enemy of the good. Can you unpack some of this for us?

DJ: Here I’m really talking about climate change policy. Climate change is not going to be prevented. It’s not even going to be mitigated to the degree a rational person would want. As a result we’re going to have to live with climate change and try to reduce the extent and rate of change as much as possible. This is not an inspiring or sexy project. There is no hero shooting a silver bullet that’s going to make it all better. The seas will continue to rise no matter who gets elected president. Even if Bill McKibben were to become dictator, future generations would suffer because of the carbon we had already emitted. This does not mean that there is nothing we can do, or no such thing as better or worse. Obama’s clean power plan, methane regulations, and increased fuel economy standards are about as good as our political system can do at this point in our history. Let’s embrace these things, make them work, and push for more, rather than denouncing them because they’re 9th best (which they are).

3:AM: Is it a mistake to argue that we’re facing unprecedented crisis, a tipping point, in terms of climate change and other environmental issues such as the next great extinction, for example?

DJ: We love apocalypse--and its true that Earth is no stranger to this. But apocalypses don’t happen very often. They tend to be separated by tens or even hundreds of millions of years. It’s possible that Lovelock was right when he predicted that we’ll screw up the climate so badly that most of us will die and a few breeding pairs will remain somewhere in the arctic. But what’s more likely is that we’ll continue remaking the planet, driving many species to extinction, killing millions of people through the indirect effects of climate change (poverty, disease, extreme events, social disruption), making life even harder for the poor and powerless than it is now, and making it a little more difficult for the global middle class to live the lives to which they have become accustomed—in other words, business as usual, only worse.

3:AM: Your latest book is a joint venture with a novelist. Does this mean that you don’t think a purely philosophical approach can get the points across?

DJ: My latest book, Love in the Anthropocene, written with Bonnie Nadzam, is an attempt to portray some of the banality of climate change. A great deal of writing about the environment is catastropharian. We wanted to show the other side. People will suffer and so will nature, but life is likely to go on with a great deal of loss and mourning. Human adaptability and resilience will still be alive, and so will that great need and resource of ours called love.

When I first started studying climate change back in the 1980s, I was struck by how difficult it was be for people to understand this issue. Climate scientists think of nothing but climate and then express their concerns in terms of constructs such as global mean surface temperature. But we live in a world in which all sorts of change is happening all the time, and the only way to understand what climate change will bring is to tell stories about how it manifests in people’s lives. In the first paper I wrote on climate change, I said that yes we need more science, but what we especially need is science fiction. Love in the Anthropocene isn’t exactly science fiction but it is fiction informed by science, and nearly thirty years after that first paper I finally got around to telling some stories—with a little help from a very talented friend.

3:AM: Science, technology, economics, politics all have big voices in the environmentalist agendas and public discourse– why should philosophers be heeded in this arena?

DJ: Sometimes I say philosophers should be at the table because they’re the only people who know that they’re not going to walk away with big money to support their research or to fund their crackpot solutions. Philosophers are smart, analytical, and skeptical. For these reasons they are relatively unbiased. Moreover, many environmental questions are in a deep way philosophical, despite our penchant for treating them as if they were only technological, economic, or whatever. Environmental problems provoke challenges about what kind of world we want, how important we think it is if something is brought about by human action or by brute nature, what we think of the value of human life compared to that of other living things. The list could obviously go on. Environmental philosophy just is philosophy full stop. It only sprung up as distinct subfield because mainstream philosophy was ignoring some of the most important philosophical challenges of our time.

3:AM: Non-human animals are an area of philosophical interest to you too aren’t they? Do we need to change the way we think about animals, in particular in terms of ethics and morality?

DJ: Yes! Yes! Yes! But here I am optimistic. Attitudes are changing very quickly. I think that by the middle of this century people will still be eating meat (though less), and their meat will mostly be produced in factories through synthetic processes, cell cultures, and so on. The idea that we would raise billions of sentient animals, treat them horribly, pollute our waterways with their waste, compromise the effectiveness of our antibiotics so that they grow faster, and then slaughter them with little regard to their suffering so that we can feed off their corpses, will seem to most people unthinkably cruel and barbarous—sort of in the way that we think of medieval punishments, or Europeans today think of the death penalty.

3:AM: So why there has been a split between environmental ethics and animal liberation historically -you'd have thought they'd have gone together. How you think they do actually fit together?

DJ: The split is deeper and more persistent than one might think, but it used to be worse. Around 1982 the editor of Environmental Ethics published an editorial discouraging papers on animal rights. There was a debate about whether concerns about the environment had anything at all to do with concerns about individual animals, and some pretty severe lines were drawn. I would go to environmental conferences and veal or prime rib would be served at the conference dinner. Many animal activists did not see why any more importance should be attached to the last mountain gorilla than to an abandoned cat in the local shelter. I eventually wrote something about this split, pointing to the high degree of overlap that exists between environmental and animal concerns, and also pointing out that deep differences exist within these communities as well. Increasingly both environmentalists and animal ethicists recognize the enormous destruction caused by animal agriculture. However, some philosophers have begun writing sympathetically about predator elimination as a way of reducing animal suffering. From an environmental perspective this is somewhere between naïve and potentially disastrous. You can’t imagine anything like nature as we know it without predators. I also worry that even well-intentioned attempts to “improve nature” (say by reducing suffering) will make things worse even in their own terms. Part of the problem, I think, is that philosophers (and probably most intellectuals) are more interested in pursuing what they see as the logical implications of their theories than they are in paying attention to the shlumpy diversity of defensible values that people actually have, and then trying to figure out how these might be negotiated in the life of an agent or community. Philosophers also tend to radically underestimate the distance between abstract principles (such as “reduce suffering”) and what it might actually mean for people to act on them. Philosophers are often actively disinterested in what happens between the cup and the lips (after all, that’s “non-ideal theory”).

3:AM: Can you say something about your notion of 'progressive consequentialism' your view of consequentialism is that it's conceptual space is vast, its plausibility varies across versions and few objections count against all versions. Could you first sketch out some of the different versions for us so we see what you're getting at. Then could you say what they all have in common and then say what the notion of 'progressive' is out to capture? Could you then say why in the case of environmentalism consequentialists should become virtue theorists?

DJ: A common rhetorical strategy of politicians and others is to frame their opponents’ views in the worst possible light, tacitly suggesting that all versions of the view must be committed to some particularly deplorable conclusion. Philosophers are not immune to this way of arguing. Kantians are saddled with absolutist views, Aristotelians are accused of vagueness, and there is almost no horror to which Consequentialists are innocent of, according to some critics. While all these families of views have been victimized in these ways, Consequentialists have gotten the worst of it. I think this may have something to do with the fact that Kant and Aristotle are acknowledged to be great philosophers, and we tend to read the greats sympathetically, while Consequentialism is a family of views not rooted in the work of a single great man to whom this kind of deference is owed. The Consequentialist trinity is typically regarded in this way: Bentham is crude, Mill’s writings are full of howlers and inconsistencies, and Sidgwickwas too smart to fully embrace Consequentialism. All of these great traditions in moral philosophy express strands of our moral consciousness and they should all be treated as research programs rather than as fully determinate views that can be leveled by a counterexample or by a clever argument.

What this means for Consequentialism is that we should see it as the family of views that holds that acts are right in virtue of the goodness of their consequences. When seen in this way it’s obvious that there are vast variety of consequentialist views, depending on what we think goodness consists in, what our notion of consequence is, and what level (or levels) of human action we think the principle should be applied. Critics of Consequentialism have often assumed that hedonism (or preference-satisfaction) must be the theory of the good, that the deontic principle must be maximizing, and that the principle should be applied to individual acts. Indeed, this version is often called “classical utilitarianism” and attributed to Bentham and sometimes even to Mill. Rather than a “classical” view it is a recent construction foisted on to the tradition. Bentham spent much of his life writing constitutions and proposing legal reform in the light of his utilitarianism. The evaluation of particular acts was hardly his concern. The psychology of his day was hedonistic and he worked in that framework and passed it on to Mill, but it is clear as day that Mill was not a hedonist in the sense in which we use that term today, though he used the language of pleasure and pain to express his views. The idea that Bentham and Mill were maximizers is the greatest stretch of all. They were progressivists, committed to improving the societies in which they lived, not utopian maximizers.

The Australian philosopher Robert Elliot and I have developed a view that we call “Progressive Consequentialism,” that we think is in the spirit of Bentham and Mill and more plausible in its own right than “classical utilitarianism.” Progressive Consequentialsm requires us to make the world better but we are under no obligation to bring about the best possible world. This view is a work in progress and there are difficult technical problems to overcome., but not only do we think that it’s a promising view in its own right, but it also illustrates the richness of the family of Consequentialist view. In my own work I’ve gone on to argue that in the face of the collective action problems that are at the heart of the environmental crisis, consequentialists should seek to inculcate the “green virtues” which includes the virtue of cooperativeness. This would not bring about the best possible world but it would set us on the path of making it better. Some philosophers think that the idea of a consequentialist virtue theory is strange, but the real strength of consequentialism is that it can emulate the requirements of other moral theories when it is the case that acting on those theories would improve the world. What most forms of Consequentialism cannot do is require us to act in such a way as to make the world worse, yet many of the objections to Consequentialism purport to show that Consequentialism requires us to make the world a stinking, bloody mess. The ubiquity of these kinds of arguments shows you just how unseriously many of the critics take Consequentialism.

3:AM: Can you say a little more about duties to the desperate - picking up on Peter Singer's arguments and the your own responses, in particular your idea that we should be more cautious about humanitarian aid programs and so forth than we are, and what principles should guide us in supporting distant people. And perhaps you could say something about Singer's practical ethics approach and whether you disagree with those who argue that his approach is too demanding.

DJ: I’m obviously very close to Singer and have learned a lot from him, but there are some differences of temperament and outlook which lead to some philosophical differences. I take seriously the idea that we are African Apes who (at least for the moment) dominate the planet, but our psychology is pretty much what it was when we were living in small groups on the savanna. We’re good at noticing sudden movements of middle size objects in our immediate visual field, but what is out of sight is for us is largely out of mind. We’re not good at noticing slow, steady changes in our environments, our senses are not very acute compared to those of many animals, and we’re pretty awful at abstract thought, much less acting on it. We’re also highly adaptable and have developed some powerful systems of representation.

Where does this leave us? First, in the broadest senses of these terms, I’m a subjectivist about morality while Singer is an objectivist. I begin with human psychology and then see what we can say about ethics. In trying to develop an impartial, expansive ethic we are trying to get ethical systems to do something which they did not evolve in order to do. This doesn’t mean that it can’t be done or that we shouldn’t try to expand the reach of our ethical frameworks, only that there are reasons to be skeptical about its success. In general I’m more skeptical than Singer about how far any of us can get out of our skins to achieve an impartial point of view, and even more skeptical about our ability to act impartially. This is a lot of what drives our disagreements about duties to the distant. Since for me moral demands necessarily flow from human psychology, I don’t think we can be obliged to do something that we are not motivated in any way to do. In other words, I’m an “internalist” about morality.

But even if we accept Singer’s very demanding principles about our duties to the distant, I think in many cases it is counter-productive or even dangerous to act on them. People and countries have done an enormous amount of damage in their attempts to bring about the best possible world. Communism is an obvious example. But so is British imperialism, which was not grubby self-interest all the way down, but at least in part a sincere attempt on the part of people who felt they were superior to other people to magnanimously improve the lot of their inferiors. In much of the world today there are no more chilling words than “I’m from the United States and I’m here to help you.” Much of the disagreement between Singer and me on this issue is empirical and very difficult to resolve in any general way. I’ve got my cases and he’s got his. We’re both reasonable people and largely accept each other’s examples of success and failure. I think what really drives the differences is that I’m a whole lot more pessimistic about our ability to maximize the good than he is. On my reading of history people who want to bring us the best are usually the people we ought to be afraid of. Still, our differences should not be exaggerated. On most issues we are comrades, and I have enormous admiration for how he has raised people’s consciousness about global poverty and preventable disease, and whatever we think of maximizing, this is important to improving the world.

3:AM: And are there five books you could recommend to the readers here at 3:AM that will take us further into your philosophical world?

DJ: Yes, but the answers may surprise people. So much of the way that I think about philosophy and the world is shaped by my encounter with Paul Ziff and my early training in philosophy of language. All of the books on my list are masterfully written, withering about stupidity, and productive of new thoughts, but that’s about all they have in common. In no particular order:

1. Paul Ziff, Semantic Analysis, constructive analytic philosophy at its best, with an account of ‘good’ that has been more influential than cited. Understanding Understandingis a good second-choice.

2. Bernard Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy, a brief for philosophical modesty and the plurality of values.

3. John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism, the best and most underrated work in nineteenth century moral philosophy, hiding in plain sight. What are often regarded as its weaknesses are its strengths--its brevity, and the fact that it was written for a broad audience. But to really appreciate the arguments, it helps to know something about Mill’s other work including the System of Logic.

4. Nelson Goodman, Problems and Projects, a masterful prose stylist takes on a variety of problems, from a distinctive and systematic point of view that celebrates pluralism and human creativity.

5. J.L. Austin, Philosophical Papers, philosophy performed before your very eyes with wit, verve, and candor. If this doesn’t make you want to do philosophy then you’re in some other business than the one I’m in.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees