Hour of The Wolf

Mark Rowlands interviewed by Richard Marshall.

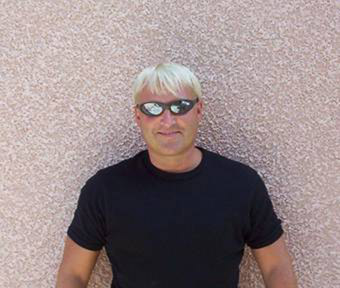

Mark Rowlands has a wild surfer look with his shades and all. At times his hair is platinum white. He once lived with a wolf and he comes from the Welsh valleys. He is always philosophising about the nature of consciousness, animal rights, applied ethics and what you can know from TV. He has written several books, including The Body in Mind, Animals Like Us, The Philosopher At The End Of The Universe, Everything I Know I Learned From TV, Fame and The Philosopher and the Wolf. He is very struck by the power of Sartre‘s line in Being and Nothingness: “All consciousness, as Husserl has shown, is consciousness of something. This means that there is no consciousness that is not a positing of a transcendent object, or if you prefer, that consciousness has no ‘content'”. This is groovy evidence that the analytic/continental divide is a dead duck.

3:AM: Were you always philosophical or has your career as a pro philosopher been something that has emerged out of your fascinating life story so far? Were you one of those young people who always brooded on the big existential issues? You’re a bit of a wild nature man of philosophy, has that anything to do with your Welsh background?

Mark Rowlands: Perceptions are funny things. I have never thought of myself as a “wild nature man of philosophy”. I suspect I’m actually not very wild at all, and if I were, it would probably have little to do with my background, which was entirely quotidian. I do think it’s likely that I’ve always had philosophical leanings. A substitute teacher once came into one of my secondary school maths classes – I think I was around fourteen at the time – and because he didn’t know maths, he decided to “entertain” us with Anselm‘s ontological argument for the existence of god (he was an religious education teacher). I didn’t buy the conclusion – god exists – but I was, nevertheless, dumbfounded by the argument’s beauty – the way in which premises combined together to yield a conclusion was something that my fourteen year-old mind had never encountered before (education in those days was more of the ‘this is the way it is and you had better believe it if you want to get on’ genre).I suspect these tendencies might be genetic. I once enthralled my father – who had no philosophical training whatsoever – with the question of whether grass is green at night. Basically, I was employing John Locke‘s idea of secondary qualities to mess with his head. My dad talked about it for days afterwards, raising arguments and objections both for and against the proposition that grass is not green at night. When I next visited him – a few months later – he was still talking about it. I thought: Aha! So that’s where I get it.

3:AM: So you are a man who lived amongst wolves – well, one wolf, at least, Brenin – for a decade. Although the account is pretty amazing and funny and moving at times there’s also a serious philosophical point being made too, isn’t there? You are challenging any account of humanity that places a critical gulf, as you put it, between humanity and other animals. Or vice versa. You kind of think that what defines us best is credulity about ourselves, and that we end up losing sight of our place in nature. Is that right? Can you say something more about all this?

MR: Brenin was sold to me as a wolf. But I think it is likely that he was a wolf-dog mix. The book was about the ways in which we differentiate ourselves from other animals – the stories we tell to convince ourselves of our superiority. Each story, I argued, has a dark side – each story casts a shadow. And in each case, what is most revealing is not the story itself, but the fact that we believe it and think it important. I focused on three common stories. The first is that we are better other animals because we are more intelligent. The second is that we are better because we have morality – we can understand right and wrong – and they do not. The third is that we are superior because we, and we alone, understand that we are going to die. Intelligence, morality and our sense of our own mortality were the three major themes of the book. I am far from convinced that to any of these stories can establish or underwrite a critical gulf between us and other animals. But, in The Philosopher and the Wolf, I was more interested in what each story reveals about us. That is, I was interested in what our valuing of these things says about us. I argued that when we dig down far enough into the roots of each of these things, we find features of ourselves that are deeply unflattering. At the roots of our intelligence we find manipulation and machination. In the roots of our morality we find power and lies. And our sense of our mortality renders us fractured creatures, unable to understand ourselves in any satisfactory way. This philosophical excavation was woven into the story of the decade or so I was fortunate enough to spend living and traveling with Brenin.

3:AM: Your book The Philosopher and the Wolf was published first in 2008. Clearly this experience is a profound one, and you write about it as an example of the storytelling facility that you think helps understand ourselves. Can you say something about the story you tell there to give readers a sense of what the book is about. You give storytelling an important place in your thinking about humans don’t you?

MR: When I was twenty-seven, I did something a really rather stupid. Actually, I almost certainly did many stupid things that year – I was, after all, twenty-seven – but this is the only one I remember because it went on to indelibly shape the future course of my life. When I first met Brenin, I was a young assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Alabama, and he was six-week old, a cuddly little teddy bear of a wolf/wolf-dog cub. Whatever he was, he grew up, and with this came various, let us call them, idiosyncrasies. If I left him unattended for more than a few minutes, he would destroy anything he could lay his jaws on – which, given that he grew to be thirty-five inches at the withers, included pretty much everything that wasn’t screwed to the ceiling. I don’t know if he was easily bored, had separation anxiety, or claustrophobia, or some combination of all of these things.But the result was that Brenin had to go everywhere I did. Any socializing I did – bars, parties, and so on – Brenin had to come too. If I went on a date, he would play the lupine gooseberry. I took him to lectures with me at the university. He would lie down and sleep in the corner of the lecture room: most of the time anyway – when he didn’t things would get interesting. I mean, you can probably imagine the circumstances that caused me to append this little cautionary note to my syllabus: “Note: Please do not pay any attention to the wolf. He will not hurt you. However, if you do have any food in your bags, please ensure that those bags are securely fastened shut.”As a result of having to share a life with a rootless and restless philosopher, Brenin became not only a highly educated wolf – the recipient of more free university education than any wolf that ever lived – but also, I suppose, a rather cosmopolitan wolf, moving with me from Alabama to Ireland, on to Wales, England, and finally to France. The Philosopher and the Wolf is the story of those years we spent together, with various philosophical musings on the differences (and similarities) between humans and other animals thrown in for good measure.

3:AM: You have a very cool riff. You say, “Some apes are more apes than others. The ‘ape’ is the tendency to understand the world in instrumental terms: the value of everything is a function of what it can do for the ape… To be alive, for the ape, is to be waiting to strike.” You argue that humans have this tendency in them because of an evolutionary event that occurred exclusively in apes. Can you say something about why you think this evolutionary bit of the story is important? It’s out of this insight that you argue that apes are basically Rawlesian contracturalist moralists? Is that right?

MR: That was the part of the book onto which the press fastened more than any other. In fact, it was the least original part of the book: a discussion of the “Machiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis” or, as it is now more commonly known, the “Social Brain Hypothesis” associated with the primatologists Richard Byrne and Andrew Whiten, among others. The basic idea is that the greater mental powers of the ape emerged out of social, rather than material, pressure. That is, rather than being the result of pressure to cope with the vicissitudes of the material world, we became more intelligent largely in order to secure social advantage: through manipulation and deception of some of our peers and forming alliances with others. Our impressive cognitive arsenal is a result of this sort of process. As I pointed out, this means that manipulation and mendacity lie at the heart of the development of our intellect. Many people were unhappy with this claim, but I don’t think it can seriously be disputed.I wouldn’t want to claim that apes are Rawlsian contractualists. That would assume they have abilities to engage in generalized reciprocity – and the existence of that in animals other than human is controversial, to say the least. My claim about Rawlsian contractualism was that it was a moral theory ideally suited to strangers – individuals who don’t really know each other very well, and don’t really care for each other very much. This sort of contractualist view grounds what we might call a morality for strangers.

3:AM: Now this is separate from your arguments for animal rights isn’t it? After all, the fact that we share some of the same mental architecture as apes doesn’t mean we necessarly have to give them rights? Or does it? Can you tell us what your basic argument is?

MR: There is a basic argument for animal rights – at least, for the claim that animals have the basic moral entitlement to have their interests counted. It’s not my argument – it’s been around a long time (although I may have played some minor role in making it more precise). The argument goes like this:1) Individual human beings possess a number of moral entitlements including, fundamentally, the entitlement to have their interests taken into account.

2) There can be no difference in the moral entitlements possessed by two individuals without there being some other relevant difference between those individuals.

3) There is no relevant difference between human and (at least some) animal individuals, where this difference is of a sort that could disqualify the latter from the fundamental entitlement to have one’s interests taken into account.

4) Therefore, some individual animals are entitled to have their interests taken into account.The idea of having one’s interests “taken into account” is not entirely clear, but is generally taken to (i) preclude a general discounting of the interests of animals, and to (ii) privilege the vital interests of animals over the non-vital interests of humans. Typically, the second claim is understand as an consequence of the first: no substantial sense can be given to the idea that an individual’s interests are being taken into account if their vital interests are routinely overridden by the non-vital interest of another individual.The argument is valid. Premises 1 and 2 are largely uncontroversial. The controversial premise is, of course, number 3. The candidates for differences that might be thought morally relevant ones correspond to properties that are either categorical in the sense that they are possessed by all human beings or characteristic in the sense that they are possessed by most, but not all, humans. Accordingly, the defense of premise 3 is a disjunctive one. The categorical properties are, most obviously, biological ones: species membership, genetic profile, and so on. However, in other contexts, the idea that biological properties are morally relevant is quickly dismissed. The argument that males possess more entitlements than females because of their different biological composition, for example, is one that few would accept.

Therefore, those whose route to the moral claims of animals is via the basic argument will typically argue that categorical differences between animals and humans are not morally relevant ones. It is not being human that is directly relevant to one’s moral standing. It is what typically or characteristically comes with being human.If this is correct, we are left with characteristic differences. The idea that these can be morally relevant is typically attacked by what has become known as, perhaps unfortunately, as the argument from marginal cases. Suppose, for example, someone were to argue that animals’ interests should be discounted on the grounds that they are not as intelligent as humans. The argument from marginal cases proceeds by pointing out that while this may be true of most humans, it is not the case for all (babies, young children, those with moderate to severe brain damage or in the advanced stages of degenerative brain conditions, and so on.) What do we say about these humans? Do we discount their interests? Eat them, experiment on them, hunt them, make them into shoes? If we assume that the answer to this question is, or should be, “no”, it means that we cannot, consistently, regard intelligence as decisive in determining whose interests are to count. The same argument applies to all the other characteristic differences between humans and animals (language use, etc).Thus, if the argument works, categorical differences are morally irrelevant, and characteristic differences fall victim to the argument from marginal cases, and therefore, ultimately turn out to be morally irrelevant also.

3:AM: You are a philosopher of mind as well as applied ethics and animal rights. This is a lively field and although there is no general consensus there are some pretty well defined disputes. You cite Shaun Gallagher as giving the rough coordinates for navigating this terrain in terms of the ‘Four Es’: embodied, embedded, enacted and extended. Can you quickly say what you take each of these things to mean?

MR: Roughly: A mental process is embodied if it is composed, in part, of processes that occur not in the brain but in the wider (that is, non-neural) body. A mental process is extended if it is composed, partly, of processes whereby a cognizing creature exploits, manipulates, or transforms relevant structures in its environment in order to accomplish a cognitive task. What makes a structure relevant is that carries information relevant to the accomplishing of the task in question, and by acting on it the cognizing creature is able to appropriate this information.A mental process is embedded or scaffolded in the wider environment if this environment plays an important (perhaps essential) role in facilitating this process’s fulfillment of its defining function (that is, if the process relies on the environment in order to work properly).A mental process is enacted if it is made up of a process of “enaction” – interaction, of the right sort, with the environment.The thesis of embedded cognition is a thesis of dependence: some cognitive processes are dependent on environmental structures or processes. The theses of embodied and extended cognition are, as I understand them, both theses of composition: some cognitive processes are partly composed of wider (i.e. non-neural) bodily and environmental processes. These are the way I use these terms. Others can use them somewhat differently, and the resulting ambiguity can lead to problems. I think the theses of embodied and extended cognition are the most radical and interesting (although the way I define the thesis of extended cognition makes it close to what many people have in mind when they think of enacted cognition.

3:AM: I thought it would be helpful if you could explain your position, which is partly that the mind is extended but you want to distinguish your position from perhaps the most well known position of the extended mind. So this is the idea that Dave Chalmers and Andy Clark defend when they say that when I take notes in my notebook the entries in the notebook are a subset of my beliefs and so are part of my mind. For many people this is ok as a metaphor, but they take it in the literal sense? Is that right?

MR: I think that some mental processes – processes such as perceiving, remembering, reasoning – can partly extend into the environment in the sense that they are partly composed of actions that subjects perform on their environment – specifically manipulation, exploitation and/or transformation of structures that carry information relevant to the solution of the task the process is supposed to accomplish. Clark and Chalmers imagine the case of Otto – a person with early stage Alzheimer’s who uses a notebook to write down information he would otherwise forget. Clark and Chalmers claim (or are widely interpreted as claiming) that when Otto writes down a sentence such as “The Museum of Modern Art is on 53rd Street’, this sentence is one of Otto’s beliefs. Their basic argument for this claim is that the sentence functions in a way relevantly similar to the way a belief would function in a healthy person’s psychology.I deny that the sentence is a belief.

I think there are several good reasons for denying this. Most importantly for me, I’m inclined to the view that intentionality is the defining feature of the mental. Intentionality is the “aboutness” of a mental state. The belief that the cat is on the mat, for example, is about a (specific) cat and its relation to a (specific) mat. This “aboutness” is what philosophers have in mind when they talk about the intentionality of thought and other mental states.The sentence in Otto’s book is not about anything in the way that a belief is about something. The sentence is just squiggles on a page – taken in itself, it could mean anything. For it to mean anything, it must be interpreted. Its intentionality or aboutness is, in this sense, merely derived. Beliefs and other mental states are not like this. You don’t first encounter the belief and then have to settle the question of what it is about. To have the belief is to be aware of what it is about. This point is sometimes put by saying that, whereas the intentionality of the sentence is derived, the intentionality of a belief is original.

Original intentionality is the hallmark of the mental. Beliefs have it, Sentences don’t. That’s why the sentences in Otto’s notebook are not beliefs.I do, however, argue that a cognitive process such as remembering can be partly composed of processes of manipulating the book – opening the pages, scanning each page, and so on – in such a way to make available the information it contains. At the core of cognition, I believe, we find processes that make available information that was previously unavailable. These processes of manipulation are part of the means whereby Otto does this.

3:AM: So their version of the extended mind emphasizes location, which you don’t. Yours is an amalgamated mind position, whereby you amalgamate all ‘four Es’. Is that right? Can you say something about what you position is and how it differs from Chalmers and Clark?

MR: I do not think that the issue of the extended mind is one of location – and for that matter is not about the mind either. First, the thesis of amalgamated cognition is one that concerns mental (specifically cognitive) processes not the mind. And no conclusions can be drawn from it about where these processes are – although some can be drawn about where they are not – at least not in their entirety.The amalgamation in question is actually that of two of the Es – embodied cognition and extended cognition – not four. I regard the theses of embodied and extended cognition as two versions of the same thing and as having the same basis (the nature of intentionality). The more interesting versions of enactivism, I argue, are in fact versions of extended cognition. The thesis of embedded cognition is far less radical than the others (indeed, in recent debates, it is often used as a neo-Cartesian fallback position to attack the other positions).

3:AM: Your position strikes some as inheriting some of the same difficulties that interpretations of Clark and Chalmers have. So one is: why does it seem counter intuitive to many and you not? Is it because common sense is pretty useless when it comes to knowing stuff that science discovers and you philosophers are trained to ignore the pull of common sense? Or does it link to your experiences with the wolf?

MR: Controversial philosophical theories sometimes have a habit of evolving into common sense. Descartes‘ view of the mind as something that is located inside the head provides a good example. I argue that the idea of extended cognition seems so outlandish because we have, for whatever reason, come to uncritically adopt a certain conception of intentionality as a process whereby the mind somehow reaches out into the world to grasp its objects. I argue that, on the contrary, intentionality is revealing activity, and as such is already out in the world. Revealing activity often straddles neural, bodily and environmental processes. So from this perspective, extended cognition is utterly mundane.

3:AM: Another objection to Clark and Chalmers is a philosophical objection that goes something like: minds don’t have parts; ergo, your notes can’t be a part of your mind? Do you think this is right and how does this affect your own position? Is that where Jesse Prinz‘s unity of mind stuff is helpful?

MR: The thesis of extended cognition, as I understand it, should not be understood as a thesis about minds. It is one about mental processes. It does not even require that there are any such things as minds, over and above mental processes. So, the objection that minds do not have parts is wide of the mark – at least given the way I understand the thesis (others understand it differently).

3:AM: I suppose the objection to Clark and Chalmers that is most powerful is that of intentionality. Mental states have content. They are about things. In a sense , that’s what defines the mental. Isn’t that the thrust of the ‘What’s it like to be a bat?’ question. So the objection is that a notebook isn’t mental because it hasn’t got content that isn’t derived from things that do have minds (i.e. us). Doesn’t this make externalism tricky? And surely this does is a problem even for your position?

MR: I agree absolutely. As I mentioned earlier, that’s the primary reason I would deny that the sentences in Otto’s notebook count as beliefs (or anything mental). The process of manipulating the book to make available the information it contains, on the other hand, is a complex process made up of, among other things, perception of the sentence on the page and beliefs formed on the basis of this perception. The perception and the resulting beliefs have original intentionality. Therefore, contained in this process is all the original intentionality one could want in a cognitive process. Therefore, my version of the theory explicitly accommodates – indeed, insists on – the original intentionality of mental things.

3:AM: Could you be interpreted as making a philosophical approach to the cognitive that is much closer to the intentionality arguments of Anscombe and McDowell. So your ‘Extended Cognitive and the Mark of the Cognitive’ paper can sound like saying cognition is just information processing, which is pretty naturalistic and a bit like Dennett, but you deny this is all. Is what you’re doing a kind of naturalised (or naturalised–sounding) Anscombe? It seems more like you’re doing a kind of conceptual analysis than the kind of thing that Dennett would contemplate. You use Brentano to discuss the transcendental mode of presentation of an object is a way of disclosure or revelation of the world and cognition. Can you say something about all this? I guess I’m really asking how much you are a naturalist and how much something different?

MR: That is a very perceptive question. Yes, I do hold the rather unfashionable view that conceptual analysis is one of the cornerstones of philosophy: one of the things – not the only by any means, but one the things – that philosophy should be doing. The mark of the cognitive was extracted by way of a process of conceptual analysis of a certain sort – analysis of the kinds of canonical models of cognitive processes employed by cognitive scientists (for example, David Marr‘s theory of vision) and what these models reveal about the sort of thing cognition must be taken to be by these theorists.To claim that philosophy is in the business of conceptual analysis is risky because it engenders much confusion. Most importantly, everyone seems to think conceptual analysis is the analysis of concepts. If I remember correctly, Timothy Williamson, in his book The Philosophy of Philosophy, argues against conceptual analysis on these grounds: concepts only make up a small fraction of what actually exists. Why would philosophy restrict itself to a small fraction of what exists? Embodied in this is a common but mistaken conception of what conceptual analysis is. Conceptual analysis is not the analysis of concepts. It is the analysis of things – conceptually. That is, the word “conceptual” functions as an adverb. One can analyze a thing – the same thing – chemically, physically, functionally and so on. So, too can one analyze it conceptually. In my mark of the cognitive, what was analyzed was a type or kind of thing: cognition. And the way in which this thing was analyzed was conceptually.Finally, the cornerstone of my view is the analysis of intentionality. I can take or leave the mark of the cognitive stuff – it is relatively unimportant to the view I want to defend (which makes it either galling or amusing, depending on what sort of mood I’m in, that almost all of the commentators have focused exclusively on it). But the analysis of intentionality – I’ll be six feet under in my cold, cold grave before I give upon that. My overall view stands or falls with the account of intentionality.

3:AM: I guess the big objection that lurks is how you get cognitive content from this? Isn’t there a general objection that you can’t derive the mental content of the mental from teleo-functional accounts. Presumably you agree but think this isn’t relevant. But then isn’t the position a bit of a cheat in that you kind of just assume the hallmark of the mental rather than explain it? Isn’t that why Searle is sometimes accused of just hand waving when he just says he knows what consciousness is and says it’s the brain? But of course, you think he’s wrong completely in that claim.

MR: The thesis of extended cognition is not an attempt to explain mental content. That is a task for other theories. The thesis is a thesis about the so-called vehicles of content: what sorts of things have content – and can be developed independently of an account of what gives them content. If the thesis of extended cognition is correct, these vehicles of content are not restricted to brain states or processes. But the thesis is not a theory about what gives these things content or why they have content.I am very tempted, as I have said, by the view that the hallmark of the mental is intentionality. The clearest examples of mental items are items that are about other things – as a belief that the cat is on the mat is about the cat and its relation to the mat. That intentionality is the hallmark or defining feature of the mental is not universally accepted. But it is a common assumption, and I believe a good one. And even if intentionality is not the defining feature of the mental, it is enough for my view that it is a very important feature of many mental states. This weaker assumption is all I really need – it gives me enough to get my central argument going.I do not know if intentionality can be naturalized. All I can say is that I have not yet seen a convincing naturalized account of it (and I include my own earlier naturalistic efforts).

Theories like the teleofunctional account (an account I once endorsed) are, I now think, predicated on the mistaken conception of intentionality that it is the task of my recent book, The New Science of the Mind, book to unseat. That is, with the teleofunctional account, and other naturalistic attempts of that ilk, one starts with an inner state – a neural configuration of some sort – and ask what conditions must be satisfied if this state is to reach out into the world and be about something. That is the wrong place to start. The right question is this: how can an object be revealed to a subject? That is, what sorts of processes are involved in an object being revealed in a given way (a tomato being revealed as red and shiny, for example).The thesis of extended cognition is true if some of these processes are ones whereby subjects act on – manipulate, transform or otherwise exploit – objects in the world. I argue that it is very implausible to suppose that revealing activity is confined to processes occurring inside skin or skull. A proper understanding of intentionality lets us see why.

3:AM: The bit of enactiveness that you integrate you develop from Husserl. Does this mean that its through phenomenology (appearance) that you understand this part of cognition. You don’t think that there are aspects of this that are extended though do you? Is that right?

MR: I think the enactive approach was almost entirely anticipated by Husserl. In his work – see especially his series of lectures published as Thing and Space – you find an account of perceptual content developed in terms of sensorimotor expectations. In Husserl also, we find at least the beginnings of the right way of thinking about intentionality – at least, there is an ambiguity in his work that can be developed in a very important and revealing way. We find essentially the same ambiguity in his contemporary, Frege. Both Husserl and Frege attributed to what they call “sense”(German: Sinn) the dual role of something that is grasped in thought, but also something that fixes reference – fixes what the thought is about. I argued that this means that in any thought, sense in its reference-fixing role, is non-eliminable. That is, whenever a subject grasps a sense (i.e. thinks a thought), there must be another sense that is not grasped. This sense, sense in its reference-fixing capacity, I argued, is best understood in terms of the idea of revealing activity. This underpins my argument for extended cognition. The vehicles of revealing activity are not, in general, exclusively neural but include bodily and environmental processes too. So, certainly, I would be happy to say that the roots of extended cognition are found in Husserl.

3:AM: How much does your attitude to animals rights link to your particular theory of the mind?

MR: Very little, I suspect. Minimal possession of moral rights is a matter of sentience, but is not dependent on any particular view of sentience. So, the thesis of extended cognition has little to do with this.

3:AM: Brenin died and you say that although your life is better than its ever been in some respects you feel diminished by his death. Can you say something about this? I was impressed by the almost mystical claims you make, as when you write , “the thoughts that drive this book are ones that I have thought but, nevertheless, are in an important sense, not mine. This is not because they are someone else’s although one can clearly discern the influence of thinkers like Nietzsche, Heidegger, Camus, Kundera, and the late Richard Taylor. Rather, and once again I must resort to metaphor, I think there are certain thoughts that can emerge only in the space between a wolf and a man. That space no longer exists. In our early days, Brenin and I used to take off some weekends to Little River Canyon in the north-eastern corner of Alabama, and (illegally) pitch a tent. We’d spend the time chilling and howling at the moon. The canyon was narrow and deep, and it was with reluctance that the sun would push its way through the dense druid oaks and birches. And once the sun had passed over the canyons western rim, the shadows would congeal into a solid bank. After an hour or so of easing ourselves along a neglected trail, we would enter into the clearing. If we had timed things just right, it would be as the sun gave its parting kiss to the canyon’s western lip, and golden light would reverberate through the open space. Then, the trees, largely hidden by the gloom for the past hour would stand out in their aged and mighty splendour. The clearing is the space that allows the trees to emerge from the darkness into the light. The thoughts that make up this book emerged in the space between one particular wolf and one particular man and would not have been possible without that space.” How different is this kind of philosophical reflection from that done as a professional philosophical? And do you think you’ll return to that state of awareness again?

MR: The Philosopher and the Wolf is a book about life – in particular, it’s about growing up. I have a book coming out next year called Running with the Pack – and that’s about growing old. (I suppose there’s a natural trilogy to be written here, but I hope I don’t have to write the third part for a while yet). For a while, philosophers abandoned these sorts of themes. Maybe they still have – I don’t know. Perhaps it was part of a perceived process of professionalization. As Julian Barnes once remarked, we are all amateurs when it comes to our own lives, and this sort of personal examination was excised in the (poorly conceived) aim of becoming a professional discipline (which basically amounted to dealing with issues and questions that only someone with an extended formal training in philosophy could understand). I think (I may be wrong) that things are changing, and this can only be a good thing. Philosophy, in the final analysis, is the art of thinking clearly. And even if we are all amateurs when it comes to our own lives, this does not preclude thinking clearly about those lives and what is important in them.

3:AM: So have there been books that have been influential to you as you brood on these he themes? You mention Kundera and Camus. Are there others?

MR: My professional training was solidly within the so-called analytic tradition in philosophy. Some might, therefore, think it strange that the biggest philosophical influences on me have been from what some people think of as “the other side” – continental philosophers. I would include Nietzsche, Husserl, Heidegger, and Sartre – all of whom have exerted significant influence on the way my thought has developed over the years. Of course, this idea of “sides” is just nonsense. The idea that one half of philosophy can afford to proceed in ignorance of what the other half is doing – that’s one of the silliest ideas philosophers have ever had (and the bar has, it goes without saying, been set quite high).3:AM: And finally, for 3:AM, which began with the strap-line ‘Hour of the Wolf’, can you give us your top five books that we should all be reading this year?

MR: One of the drawbacks of spending virtually all of one’s time writing is that one never has the time to read, not properly. One skims, and gets as much out of a book as one needs for one’s own purposes. It’s very sad. So, I’m sorry, but I haven’t a clue what we should be reading. For my part, however, when I can find the time, I’m looking forward to reading:

Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, Zoopolis

Christof Koch‘s, Consciousness: Confessions of a Romantic ReductionistRecently, I have learned a lot from:

Marc Bekoff and Jessica Pierce, Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals

Colin Allen and Wendall Wallach, Moral Machines: Teaching Robots Right From Wrong

Frans de Waal, The Age of Empathy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Marshall is still biding his time.